In 1926, after having already squandered several million dollars on the fabled Ben Hur, executives at MGM studio decided to start from scratch. The lead in Ben Hur was of the most coveted parts in Hollywood history. The part was given to Ramon Novarro, and remains the film for which he is best remembered.

In 1926, after having already squandered several million dollars on the fabled Ben Hur, executives at MGM studio decided to start from scratch. The lead in Ben Hur was of the most coveted parts in Hollywood history. The part was given to Ramon Novarro, and remains the film for which he is best remembered.It had been a long and tough road for the 27-year-old actor, who was born Ramon Samaniego in Durango, Mexico, in 1899. He came from a cultivated family (his father was a successful dentist), but the 1910 Mexican Revolution caused the family to flee to the U.S., where they lived in poverty for the following decade.

Ramon worked at a number of menial jobs to help his family, and to support himself. He moved to New York, working as a singing waiter, and as an usher in a movie house. He was ''spotted'' by an agent and offered a short-term contract.

Ramon worked at a number of menial jobs to help his family, and to support himself. He moved to New York, working as a singing waiter, and as an usher in a movie house. He was ''spotted'' by an agent and offered a short-term contract.There seems to be some dispute as to when he began appearing in movies, because many silent motion pictures of that time no longer exist, and bit players were a dime a dozen. Novarro's first film appearance was most likely in The Woman God Forgot in 1917, according to his biographer Andre Soares. So, before The Little American in 1918, with Wallace Beery and Mary Pickford. His breakthrough film, however, was The Prisoner of Zenda, co-starring with Alice Terry, the wife of Rex Ingram, the director. Ingram suggested that Ramon change his last name to Novarro. Ingram then directed Novarro in a series of films, including 1922's Scaramouche also featuring Alice Terry.

There are some who refer to Novarro as a new Valentino, because of the latin lover phase Hollywood went through, but Novarro was more than that. He had a fine singing voice, which made him one of the few stars of the silent film era to seamlessly make the transition to sound. However, Valentino was one of Novarro's closest friends. At MGM, Novarro's salary reached $10,000 a week – a fabulous sum in the 1920s – which allowed him to invest in real estate. His first ''talking'' picture was MGM's Devil May Care in 1929.

There are some who refer to Novarro as a new Valentino, because of the latin lover phase Hollywood went through, but Novarro was more than that. He had a fine singing voice, which made him one of the few stars of the silent film era to seamlessly make the transition to sound. However, Valentino was one of Novarro's closest friends. At MGM, Novarro's salary reached $10,000 a week – a fabulous sum in the 1920s – which allowed him to invest in real estate. His first ''talking'' picture was MGM's Devil May Care in 1929.In later years Novarro had little good to say about the talking pictures he starred in. When he was interviewed by DeWitt Bodeen, for Films in Review, in the late 1960s, he said : "With the exception of The Pagan, in which I only sing... and some of Song of India, and a good part of Feyder's Daybreak – certainly not the ending however – I didn't like any of the talkies in which I starred.'' He didn't even mention 1932's Mata Hari, in which he co-starred with Greta Garbo. Novarro seemed to be refreshingly free of the egotism that is so rampant in the film industry.

In 1923, Louella Parsons, the most powerful gossip columnist in Hollywood, wrote of Novarro, in the New York Morning Telegraph: "And come to think of it, why shouldn't Ramon be an optimist. At 23 he is earning a salary of $1,250 a week, with the possibility of increasing to $4,000 and $5,000 next year. Coming from Durango, Mexico, he entered a stock company in San Francisco and played small parts. Among other things he did the Italian doctor in Enter Madame. He learned every part in every play with an avidity that brought him the admiration of his teacher and fellow pupils. Betty Blythe tells of studying in the same class with the young Novarro and of seeing him in one day play three different parts in the same production, doing each one with equal skill.

In 1923, Louella Parsons, the most powerful gossip columnist in Hollywood, wrote of Novarro, in the New York Morning Telegraph: "And come to think of it, why shouldn't Ramon be an optimist. At 23 he is earning a salary of $1,250 a week, with the possibility of increasing to $4,000 and $5,000 next year. Coming from Durango, Mexico, he entered a stock company in San Francisco and played small parts. Among other things he did the Italian doctor in Enter Madame. He learned every part in every play with an avidity that brought him the admiration of his teacher and fellow pupils. Betty Blythe tells of studying in the same class with the young Novarro and of seeing him in one day play three different parts in the same production, doing each one with equal skill.

Rex Ingram came upon Novarro and cast him as Rupert of Hentzau in The Prisoner of Zenda. The boy before he met Mr. Ingram had been struggling under the handicap of a name like Samanegas [sic]. Mr. Ingram rechristened him, helped him and gave him the chance that was later going to get him many offers from film companies. And young Novarro isn't going to bite the hand that fed him. Not Ramon ; if Mr. Ingram wanted his last cent he could have it. "Rex Ingram is a wonderful director," said Ramon in a voice that should be worth his fortune if Spanish accents are being used this year. And it's real, too. If any one doesn't think Rex Ingram is a great man, Ramon is ready to fight with him. We agreed with Ramon on the Ingram question, and so we were rewarded with a smile.

Rex Ingram came upon Novarro and cast him as Rupert of Hentzau in The Prisoner of Zenda. The boy before he met Mr. Ingram had been struggling under the handicap of a name like Samanegas [sic]. Mr. Ingram rechristened him, helped him and gave him the chance that was later going to get him many offers from film companies. And young Novarro isn't going to bite the hand that fed him. Not Ramon ; if Mr. Ingram wanted his last cent he could have it. "Rex Ingram is a wonderful director," said Ramon in a voice that should be worth his fortune if Spanish accents are being used this year. And it's real, too. If any one doesn't think Rex Ingram is a great man, Ramon is ready to fight with him. We agreed with Ramon on the Ingram question, and so we were rewarded with a smile.Another hero to young Novarro is Marcus Loew.

''You had many offers,'' we asked him, ''to make pictures?''

''Yes, many, but I would not leave Mr. Loew. Do you think I would be so ungrateful?''

We looked about for smelling salts after this noble declaration ; it was so unusual. The average motion picture male star who has reached the top in a few bounds usually spends his time telling the interviewer what a bum his director is and how little he knows and what a raw deal he got with his company, but Ramon isn't following the usual prescribed path. He is grateful and he doesn't care who knows it.''

We looked about for smelling salts after this noble declaration ; it was so unusual. The average motion picture male star who has reached the top in a few bounds usually spends his time telling the interviewer what a bum his director is and how little he knows and what a raw deal he got with his company, but Ramon isn't following the usual prescribed path. He is grateful and he doesn't care who knows it.''After starring in a number of musicals for MGM (a staple of that studio), and being badly miscast in a series of films, Novarro decided to get out. Over the following years he appeared on the stage, sang, directed several films – and tended to his investments. He made a brief return to movies – unsuccessfully, and appeared on television a number of times. He told Dewitt Bodeen he was writing an autobiography, but that it might not be possible to publish it until after his death. He said in that interview that, in the 1920s, many stars were allowed their privacy – that the details of their personal lives were not published unless they sought it.

There were many in 1920s Hollywood who knew Novarro was homosexual, but he was widely considered a gentleman, a class act that kept his private life private – until October 30, 1968.

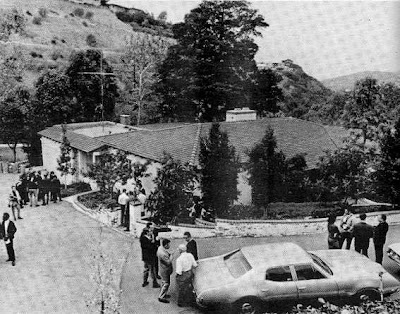

There were many in 1920s Hollywood who knew Novarro was homosexual, but he was widely considered a gentleman, a class act that kept his private life private – until October 30, 1968.On that date the 69-year-old Novarro took two street hustlers, brothers Paul and Tom Ferguson, to his Laurel Canyon home. Apparently he'd been seeing 22-year-old Paul for several weeks, and 17-year-old Tom had shown up in town.

The gentle Novarro would undergo terrible tortures in the next few hours, because Paul Ferguson believed the aging actor had thousands of dollars hidden away in his house. As the torture was underway, young Tom used a telephone in a different room to call a girlfriend in Chicago. He told her they were at Navarro's home, and that Paul was trying to find out where some money was. That phone conversation went on for more than 40 minutes. At one point Tom put the phone down, saying he'd better check on Paul to make sure he wasn't hurting Ramon, and the girl on the other end could hear screams in the background.

When Novarro's body was found next morning, hundreds of pictures had been ripped from the walls, in a desperate search by the Fergusons to find the fabled money – which didn't exist. On a hunch, the L.A.P.D. checked the phone logs for Novarro's home phone, and discovered a call to Chicago the previous evening. When they called that number, they talked to the young girl and she told them everything.

When Novarro's body was found next morning, hundreds of pictures had been ripped from the walls, in a desperate search by the Fergusons to find the fabled money – which didn't exist. On a hunch, the L.A.P.D. checked the phone logs for Novarro's home phone, and discovered a call to Chicago the previous evening. When they called that number, they talked to the young girl and she told them everything.After their arrest, Paul Ferguson convinced his younger brother to confess to the crime, on the theory that, as a juvenile, Tom would only face a year or so in jail, whereas Paul would be facing the gas chamber. So Tom Ferguson confessed to the murder. Then the prosecutor moved to have Tom Ferguson tried as an adult – rather than as a juvenile. When the court granted that motion, Tom Ferguson immediately recanted his confession. During their joint trial, each Ferguson maintained that the other had tortured and killed Ramon Novarro.

Paul Ferguson’s defense attorney, Cletus Hanifin, in reference to Novarro’s numerous drunken driving episodes — which had begun at least as early as the 1940s — blamed the victim for his brutal death. "For forty years," Hanifin told the jury, "Novarro had been an accident walking around looking for a place to happen."

Tom’s defense attorney, Richard Walton, also placed the blame on Novarro. "Back in the days of Valentino, this man who set female hearts aflutter, was nothing but a queer. There’s no way of calculating how many felonies this man committed over the years, for all his piety." The Mexican-born Novarro was an ardent Catholic; Walton was also referring to the fact that Tom was a minor when he was invited to Novarro’s home and that homosexual acts were illegal in California at that time.

District attorney James Ideman blamed the Fergusons, accusing them of killing, beating, and torturing Novarro in order to find out the whereabouts of $5,000 the actor supposedly kept in his music room. There was no money; the music room had cost $5,000.

District attorney James Ideman blamed the Fergusons, accusing them of killing, beating, and torturing Novarro in order to find out the whereabouts of $5,000 the actor supposedly kept in his music room. There was no money; the music room had cost $5,000.Paul Ferguson blamed his Catholic background. "When [Novarro] kissed me, I reacted like a Catholic, what they call homosexual panic. Some old guy in the desert says, ‘Kill homosexuals.’ It’s inbred... I was too drunk to be civilized. Whatever my most primitive moral standings were, I reacted. It had nothing to do with Novarro, nothing to do with his being homosexual. It all had to do with how I saw myself. And the fact that my brother was there. And that he could see me in that homosexual act. It all had to do with my Catholic upbringing, with my five thousand years of Moses. And that’s the only reason why this whole thing happened. Because that’s what society teaches you... I think after I hit Mr. Novarro... I turned around and sat down on the sofa. I got up and went to find [Novarro] in the bedroom. ‘This guy’s dead.’... We didn’t go there to rob him" (from Andre Soares' Beyond Paradise : The Life of Ramon Novarro - highly recommended).

Each Ferguson was sentenced to life imprisonment – even though the authorities had discounted young Tom's confession. Not much is known of what became of Tom Ferguson. He appears to have gotten out of prison and blended into the American woodwork. If he was, as he claimed, innocent of the murder of Novarro, then he didn't have to change all that much in order to go straight when he got out.

Each Ferguson was sentenced to life imprisonment – even though the authorities had discounted young Tom's confession. Not much is known of what became of Tom Ferguson. He appears to have gotten out of prison and blended into the American woodwork. If he was, as he claimed, innocent of the murder of Novarro, then he didn't have to change all that much in order to go straight when he got out.sources :

http://crimemagazine.com/Celebrities/ramonnov.htm

http://www.altfg.com/blog/actors/ramon-novarro-death/

1 commentaire:

Hello,

A few corrections to your text:

Ramon Novarro was born Ramon Samaniego, not Samaniegos. I've seen his birth certificate.

Novarro's first film appearance was most likely in "The Woman God Forgot" (1917). Confusion has arisen because DeWitt Bodeen was a *very* unreliable chronicler.

The Paul Ferguson quote you use in your article, "When Novarro kissed me..." was taken from my Novarro biography BEYOND PARADISE: THE LIFE OF RAMON NOVARRO. You should have said so in the text.

Andre Soares

Enregistrer un commentaire