Among the myths associated with the 1920s, the flamboyance of style is the most persistent. [...] Most homosexuals wanted [...] to blend in with the mass of "normal" people and so they conformed to the canons of virility that were in vogue at the timen adding only the slightest variations to their appearance. [...] The "serious, intelligent and embarrassed homosexual" dit not distinguish himself in any way. The hair was worn very short at the nape of the neck and on the sides, brillantined and combed in order to form a wave or plastered smooth like patent leather. The suit was dark, of thick fabric, broad in cut, with the bottom of the trousers flared. This baggy fashion had some erotic advantages, as Gifford Skinner relates : "The average man wore his trousers very full cut and they went up almost to the chest. The underclothers, if one wore any, were quite as loose and left the genitals free. Any friction caused by walking could produce the most stark effect. In the street, homosexuals would stud their conversation with remarks like 'Did you see that piece?' or 'Look what's coming - he's sticking straight out!' This was often an illusion caused by a fold in the clothing, but it was a pleasant pastime and didn't cost anything."

Among the myths associated with the 1920s, the flamboyance of style is the most persistent. [...] Most homosexuals wanted [...] to blend in with the mass of "normal" people and so they conformed to the canons of virility that were in vogue at the timen adding only the slightest variations to their appearance. [...] The "serious, intelligent and embarrassed homosexual" dit not distinguish himself in any way. The hair was worn very short at the nape of the neck and on the sides, brillantined and combed in order to form a wave or plastered smooth like patent leather. The suit was dark, of thick fabric, broad in cut, with the bottom of the trousers flared. This baggy fashion had some erotic advantages, as Gifford Skinner relates : "The average man wore his trousers very full cut and they went up almost to the chest. The underclothers, if one wore any, were quite as loose and left the genitals free. Any friction caused by walking could produce the most stark effect. In the street, homosexuals would stud their conversation with remarks like 'Did you see that piece?' or 'Look what's coming - he's sticking straight out!' This was often an illusion caused by a fold in the clothing, but it was a pleasant pastime and didn't cost anything." Others, however, sought a departure from the ubiquitous classicism. Suits in electric blue, almond green or old rose were much admired, but few dared to wear them for fear of being kicked out of public places. Certain accessories became homosexual signs of recognition, in particular suede shoes and camel's hair coats. Some dared to wear their hair long. Any eccentricity was readily perceived as proof of inversion, leading to a little adventure for Quentin Crisp, a flagrant homosexual if ever there was one, when he presented himself at the draft board : While his eyes were being tested, they said to him, "You've dyed your hair. That's a sign of sexual perversion. Do you know what these words mean?" He just said yes, and that he was a homosexual. That does not mean that the man in the street could clearly identify a homosexual that he knew enough to decipher the signs. However, any sartorial oddity was suspicious and could easily be seen as a sign of homosexuality. There was one way out : to be perceived as an artist, i.e. necessarily an "original". Crisp notes that the sexual significance of certain forms of comportment was understood only vaguely, but the sartorial symbolism was recognized by everyone. Wearing suede shoes inevitably made you suspect. Anyone whose hair was a little raggedy at the nape of the neck was regarded as an artist, a foreigner, or worse yet. One of his friends told him that, when someone introduced him to an older gentleman as an artist, the man said : "Oh, I know his young man is an artist. The other day I saw him on the street in a brown jacket." In the same way, the use of make-up was spreading, so that mere possession of a powder puff was enough to prove one's homosexuality for the police.

Others, however, sought a departure from the ubiquitous classicism. Suits in electric blue, almond green or old rose were much admired, but few dared to wear them for fear of being kicked out of public places. Certain accessories became homosexual signs of recognition, in particular suede shoes and camel's hair coats. Some dared to wear their hair long. Any eccentricity was readily perceived as proof of inversion, leading to a little adventure for Quentin Crisp, a flagrant homosexual if ever there was one, when he presented himself at the draft board : While his eyes were being tested, they said to him, "You've dyed your hair. That's a sign of sexual perversion. Do you know what these words mean?" He just said yes, and that he was a homosexual. That does not mean that the man in the street could clearly identify a homosexual that he knew enough to decipher the signs. However, any sartorial oddity was suspicious and could easily be seen as a sign of homosexuality. There was one way out : to be perceived as an artist, i.e. necessarily an "original". Crisp notes that the sexual significance of certain forms of comportment was understood only vaguely, but the sartorial symbolism was recognized by everyone. Wearing suede shoes inevitably made you suspect. Anyone whose hair was a little raggedy at the nape of the neck was regarded as an artist, a foreigner, or worse yet. One of his friends told him that, when someone introduced him to an older gentleman as an artist, the man said : "Oh, I know his young man is an artist. The other day I saw him on the street in a brown jacket." In the same way, the use of make-up was spreading, so that mere possession of a powder puff was enough to prove one's homosexuality for the police.

[...] The very chic Stephen Tenant (1906-1987), taking tea with his aunt, was admonished : "Stephen darling, go and wash your face." Thus we know that the practice was by no means limited to male prostitutes, but involved various social classes. However, it was far from being well accepted, even in the most exalted circles. At a ball hosted by the Earl of Pembroke, Cecil Beaton was thrown in the water by some of the more virile young men; one of them shouted : " Do you think the fag drowned?" According to Tennant, who was there at the time, the attack was caused by the abuse of make-up ; he was convinced that it was Beaton's made-up that so disturbed the thugs. When Stephen Tennant was a little boy in Edwardian England, his father asked him what he would like to be when he grew up. "I want to be a Great Beauty, Sir," he replied. In the 1920s, Stephen Tennant embodied homosexual aesthetics carried to its apogee. He was a great beauty, and he enjoyed using all the artifices of seduction and l'art de la pose, theatricality. In that, he exaggerated the prevailing fashion for dressing up.[...] Photographed by Cecil Beaton, especially, Tennant looked like a prince charming. Even in his everyday wear, he stood apart from the crowd ; [...] his style and his innate sense of theater [...] made him a symbol of the Bright Young People of the 1920s in London. Late in the decade, Tennant represented the most extrem of fashion - for a man, at least. His feminine manners and appearance were not diminished by the striped double-breasted suits he wore, in good taste and well cut, "which ought to have made him resemble any young fellow downtown." But Stephen's physical presence was enough to belie such an impression. He was large and imperious, but he moved with a pronounced step, affected, which was drescribed as "prancing" or as "seeming to be attached at the knees".

[...] The very chic Stephen Tenant (1906-1987), taking tea with his aunt, was admonished : "Stephen darling, go and wash your face." Thus we know that the practice was by no means limited to male prostitutes, but involved various social classes. However, it was far from being well accepted, even in the most exalted circles. At a ball hosted by the Earl of Pembroke, Cecil Beaton was thrown in the water by some of the more virile young men; one of them shouted : " Do you think the fag drowned?" According to Tennant, who was there at the time, the attack was caused by the abuse of make-up ; he was convinced that it was Beaton's made-up that so disturbed the thugs. When Stephen Tennant was a little boy in Edwardian England, his father asked him what he would like to be when he grew up. "I want to be a Great Beauty, Sir," he replied. In the 1920s, Stephen Tennant embodied homosexual aesthetics carried to its apogee. He was a great beauty, and he enjoyed using all the artifices of seduction and l'art de la pose, theatricality. In that, he exaggerated the prevailing fashion for dressing up.[...] Photographed by Cecil Beaton, especially, Tennant looked like a prince charming. Even in his everyday wear, he stood apart from the crowd ; [...] his style and his innate sense of theater [...] made him a symbol of the Bright Young People of the 1920s in London. Late in the decade, Tennant represented the most extrem of fashion - for a man, at least. His feminine manners and appearance were not diminished by the striped double-breasted suits he wore, in good taste and well cut, "which ought to have made him resemble any young fellow downtown." But Stephen's physical presence was enough to belie such an impression. He was large and imperious, but he moved with a pronounced step, affected, which was drescribed as "prancing" or as "seeming to be attached at the knees".

Each of his movements, from the facial muscles to his long limbs, seemed calculated for effect. He gilded his fair hair with a sprinkling of gold dust, and used certain preparations to hold the dark roots in check. "Stephen could very well have been taken for a Vogue illustration - perhaps by Lepappe - brought to life." [...] Together with Cecil Beaton, Stephen Tennant and other young society men organized all kinds of themed evenings. Stephen Tennant's effeminate appearance caused ambivalent reactions. Some were simply struck : "I do not know if that is a man or a woman, but it is the most beautiful creature I have ever seen", the admiral Sir Lewis Clinton-Baker would say. Others were less indulgent. When Tennant arrived one evening dressed particularly outrageously, the criticism reached a boiling point. Rex Whistler, one of his friends, considered it regrettable that he had gone too far : "He posed as much as a girl." Rex's brother added, "Men should not draw attention to themselves. That was the only true charge against Stephen, and it was irrefutable." Parents also complained that their children spent time with Stephen. Edith Olivier noted that Helena Folkestone was complaining about how badly people spoke of Stephen, that he was hated by people who did not understand him. Olivier noted that they were out of touch with the times, since "nowadays so many boys resemble girls without being effeminate. That is the kind of boys that have grown up since the war."

Each of his movements, from the facial muscles to his long limbs, seemed calculated for effect. He gilded his fair hair with a sprinkling of gold dust, and used certain preparations to hold the dark roots in check. "Stephen could very well have been taken for a Vogue illustration - perhaps by Lepappe - brought to life." [...] Together with Cecil Beaton, Stephen Tennant and other young society men organized all kinds of themed evenings. Stephen Tennant's effeminate appearance caused ambivalent reactions. Some were simply struck : "I do not know if that is a man or a woman, but it is the most beautiful creature I have ever seen", the admiral Sir Lewis Clinton-Baker would say. Others were less indulgent. When Tennant arrived one evening dressed particularly outrageously, the criticism reached a boiling point. Rex Whistler, one of his friends, considered it regrettable that he had gone too far : "He posed as much as a girl." Rex's brother added, "Men should not draw attention to themselves. That was the only true charge against Stephen, and it was irrefutable." Parents also complained that their children spent time with Stephen. Edith Olivier noted that Helena Folkestone was complaining about how badly people spoke of Stephen, that he was hated by people who did not understand him. Olivier noted that they were out of touch with the times, since "nowadays so many boys resemble girls without being effeminate. That is the kind of boys that have grown up since the war."

Although many who knew Tennant later in life "could hardly believe the physical act possible for him", The one real love affair of his adult life was with Siegfried Sassoon (1886-1967), the masculine, renowned pacifist poet. Sassoon brought to their relationship his fame, his talent, his position, while Tennant's only daily activities were dressing-up and reading about himself in the gossip columns. Looking at the photos of the two lovers, Tennant posing languidly (vogueing, really), way-too-thin and way-too-rich, as Sassoon looks on proudly, even the most radical Act-Up militant might mutter a private "Oh, brother!" However Tennant's extreme elegance was close to sexual terrorism, as it flabbergasted society on both sides of the Atlantic for half a century. "Cherish me and introduce me to the glories of New York," Tennant telephoned a startled friend, David Herbert, as he crossed the Atlantic on the Berengaria. Herbert met Tennant at the boat and was embarrassed to see him walking down the gangway "marcelled and painted [...] delicately holding a spray of cattleya orchids."Pin 'em on!" shouted a tough customs officer in homophobic disgust."Oh, have you got a pin?" exclaimed Tennant in complete disregard for the reaction of others. "You kind, kind creature."

Although many who knew Tennant later in life "could hardly believe the physical act possible for him", The one real love affair of his adult life was with Siegfried Sassoon (1886-1967), the masculine, renowned pacifist poet. Sassoon brought to their relationship his fame, his talent, his position, while Tennant's only daily activities were dressing-up and reading about himself in the gossip columns. Looking at the photos of the two lovers, Tennant posing languidly (vogueing, really), way-too-thin and way-too-rich, as Sassoon looks on proudly, even the most radical Act-Up militant might mutter a private "Oh, brother!" However Tennant's extreme elegance was close to sexual terrorism, as it flabbergasted society on both sides of the Atlantic for half a century. "Cherish me and introduce me to the glories of New York," Tennant telephoned a startled friend, David Herbert, as he crossed the Atlantic on the Berengaria. Herbert met Tennant at the boat and was embarrassed to see him walking down the gangway "marcelled and painted [...] delicately holding a spray of cattleya orchids."Pin 'em on!" shouted a tough customs officer in homophobic disgust."Oh, have you got a pin?" exclaimed Tennant in complete disregard for the reaction of others. "You kind, kind creature." In London, sollicitation principally took the form of "cottaging"; it consisted in making the rounds of the various urinals of the city looking for quick and anonymous meetings. [...] The urinals were frequently subjected to police raids; and there were often agents provocateurs, which made it all the more dangerous. Then other places were used used as pick-up sites, like the arcades of the County Fire Office in Piccadilly Circus, the Turkish baths at Jermyn Street, the isolated streets [...] ; in Clareville Street, Leicester Public garden or Grosvenor Hill, one could find somebody for the night. [...] As in Germany, but to a lesser degree, male prostitution expanded tue to unemployment. At the Cat and Flute in Charing Cross, young workmen would be found. The contemporary practice was that two would sit together and share a beer. A client would approach and offer to pay for the second one. After a moment one of the boys would step away, leaving the two others together. These boys were not necessarily homosexual, but got into prostitution due to the econoic situation. Some of them said they were "saving up to get married." The rates were set, with 10 shillings added if there were sodomy. Soldiers (mainly from the Guards brigad) and sailors made up another category of prostitutes. Unlike the workmen, they were not in prostitution as a result of need but rather by tradition. The best places to meet them were the London parks, [...] Tattersall Tavern in Knightsbridge, and The Drum, by the Tower of London, for sailors. The guards' red uniform and the sailors' costumes exerted a fascination and an erotic attraction that was constantly evoked by contemporaries: "everyone prefers something in uniform." Any national costume or traditional equipment can be sexually stimulating and there are as many eccentric sexual tastes as there are kinds of costumes.

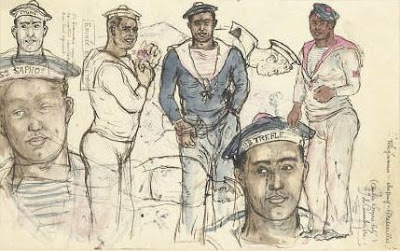

In London, sollicitation principally took the form of "cottaging"; it consisted in making the rounds of the various urinals of the city looking for quick and anonymous meetings. [...] The urinals were frequently subjected to police raids; and there were often agents provocateurs, which made it all the more dangerous. Then other places were used used as pick-up sites, like the arcades of the County Fire Office in Piccadilly Circus, the Turkish baths at Jermyn Street, the isolated streets [...] ; in Clareville Street, Leicester Public garden or Grosvenor Hill, one could find somebody for the night. [...] As in Germany, but to a lesser degree, male prostitution expanded tue to unemployment. At the Cat and Flute in Charing Cross, young workmen would be found. The contemporary practice was that two would sit together and share a beer. A client would approach and offer to pay for the second one. After a moment one of the boys would step away, leaving the two others together. These boys were not necessarily homosexual, but got into prostitution due to the econoic situation. Some of them said they were "saving up to get married." The rates were set, with 10 shillings added if there were sodomy. Soldiers (mainly from the Guards brigad) and sailors made up another category of prostitutes. Unlike the workmen, they were not in prostitution as a result of need but rather by tradition. The best places to meet them were the London parks, [...] Tattersall Tavern in Knightsbridge, and The Drum, by the Tower of London, for sailors. The guards' red uniform and the sailors' costumes exerted a fascination and an erotic attraction that was constantly evoked by contemporaries: "everyone prefers something in uniform." Any national costume or traditional equipment can be sexually stimulating and there are as many eccentric sexual tastes as there are kinds of costumes. The sailors' uniform was particularly appreciated for the tight fit and especially for the horizontal fly. Moreover, while soldiers generally had very little time to share, sailors had many weekends. For a walk in the park, a soldier received about 2 shillings ; a silor might get up to 3 pounds. Stephen Tennant wrote about this fascination, nothing one sailor's tight little derière. Anecdotes from those days include the story of an evening organized by Edward Gathorne-Hardy where a contingent of soldiers of the Guard were invited as special guests ; in another, a soldier was offered as a gift to the master of the house. To the soldiers, prostitution was a tradition ; it seems that the young recruits were initiated by the elders as they were being integrated into the regiment. The customers were designated twanks, steamers or fitter's mates. A good patron was preferred ; thus Ackerley reveived a letter one day announcing the death of one of his lovers - and another soldier from his regiment offering himself as a replacement. This part-time prostitution allowed soldiers to get some pocket money, which they then spent on drinks or with prostitutes of their own. These activities were not entirely safe, for many a soldier or sailor could turn out to be quite brutal.

The sailors' uniform was particularly appreciated for the tight fit and especially for the horizontal fly. Moreover, while soldiers generally had very little time to share, sailors had many weekends. For a walk in the park, a soldier received about 2 shillings ; a silor might get up to 3 pounds. Stephen Tennant wrote about this fascination, nothing one sailor's tight little derière. Anecdotes from those days include the story of an evening organized by Edward Gathorne-Hardy where a contingent of soldiers of the Guard were invited as special guests ; in another, a soldier was offered as a gift to the master of the house. To the soldiers, prostitution was a tradition ; it seems that the young recruits were initiated by the elders as they were being integrated into the regiment. The customers were designated twanks, steamers or fitter's mates. A good patron was preferred ; thus Ackerley reveived a letter one day announcing the death of one of his lovers - and another soldier from his regiment offering himself as a replacement. This part-time prostitution allowed soldiers to get some pocket money, which they then spent on drinks or with prostitutes of their own. These activities were not entirely safe, for many a soldier or sailor could turn out to be quite brutal.from History Of Homosexuality In Europe, 1919-1939 par Florence Tamagne

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire